Legends

Legends Hold on Tight

Hold on Tight Just a Little Bit Guilty

Just a Little Bit Guilty The Beloved Woman

The Beloved Woman Alice At Heart

Alice At Heart Heart of the Dragon

Heart of the Dragon Critters of Mossy Creek

Critters of Mossy Creek Diary of a Radical Mermaid

Diary of a Radical Mermaid Caught by Surprise

Caught by Surprise Stranger in Camelot

Stranger in Camelot At Home in Mossy Creek

At Home in Mossy Creek Charming Grace

Charming Grace Blue Willow

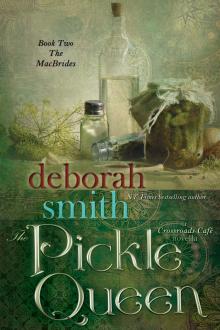

Blue Willow The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella

The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella On Bear Mountain

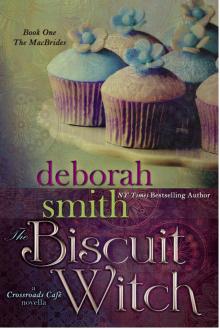

On Bear Mountain The Biscuit Witch

The Biscuit Witch Sara's Surprise

Sara's Surprise More Sweet Tea

More Sweet Tea The Apple Pie Knights

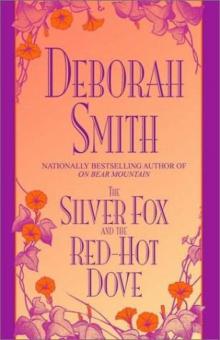

The Apple Pie Knights The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove

The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove Sweet Hush

Sweet Hush California Royale

California Royale Hot Touch

Hot Touch Miracle

Miracle The Stone Flower Garden

The Stone Flower Garden A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home Silk and Stone

Silk and Stone Honey and Smoke

Honey and Smoke Jed's Sweet Revenge

Jed's Sweet Revenge Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove

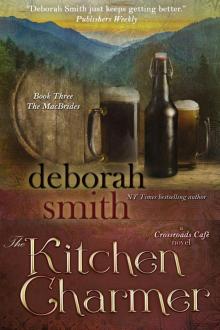

Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove The Kitchen Charmer

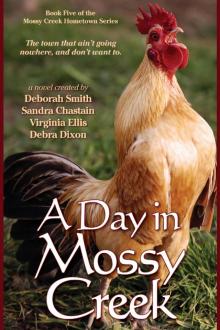

The Kitchen Charmer A Day in Mossy Creek

A Day in Mossy Creek Never Let Go

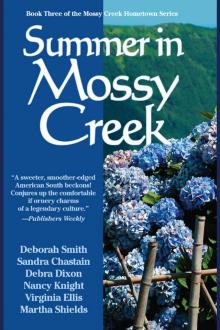

Never Let Go Summer in Mossy Creek

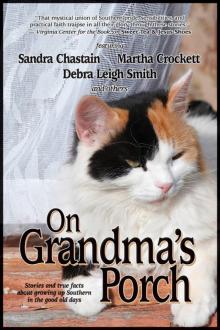

Summer in Mossy Creek On Grandma's Porch

On Grandma's Porch The Crossroads Cafe

The Crossroads Cafe Follow the Sun

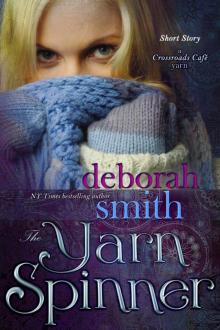

Follow the Sun The Yarn Spinner

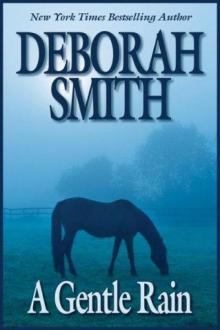

The Yarn Spinner A Gentle Rain

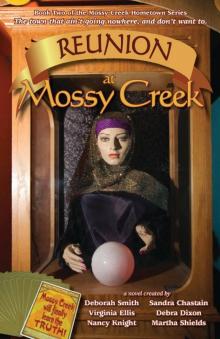

A Gentle Rain Reunion at Mossy Creek

Reunion at Mossy Creek