- Home

- Deborah Smith

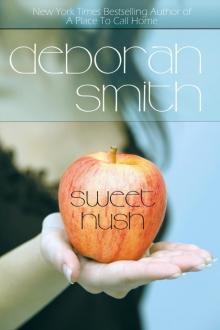

Sweet Hush

Sweet Hush Read online

Promo Page

Romance, mystery, family drama, and an apple-throwing fight with the First Lady. Welcome to Hush McGillan’s world, where the new in-laws live in the White House, the most irresistible man she’s ever met is the President’s nephew, and her most painful secrets may soon be exposed to the world.

Her Harvard-student son just eloped with the First Daughter. CNN is parked on the road to her apple orchards. Secret Service agents have commandeered her country kitchen. The irate First Parents are threatening to have her taxes audited. The President’s handsome, tough, ex-military nephew is setting up camp in her guest room. Hush McGillan’s quiet Appalachian world of heirloom apples, country festivals, and carefully guarded family secrets has just been flipped like one of her famous Sweet Hush Apple Turnovers. What do you do when your brand-new in-laws are the First Family, and they don’t like you any more than you like them? And what happens next when you find yourself falling in love with the man they sent to unearth all your secrets? From the White House to the apple house, from humor to tears and sorrow to laughter, get ready to fall in love with Sweet Hush. Optioned for Disney Films by the producer of The Princess Diaries. Deborah Smith is the New York Times bestselling author of A Place To Call Home, The Crossroads Cafe, A Gentle Rain and many others. Visit her at www.bellebooks.com and www.deborah-smith.com.

*

Full of enchanting folklore and southern charm, Smith’s latest is a beautifully written and touching tale.

—BOOKLIST

The Novels of Deborah Smith

From Bell Bridge Books

Sweet Hush

On Bear Mountain

The Stone Flower Garden

Charming Grace

The Crossroads Café

A Gentle Rain

Alice at Heart

Diary of a Radical Mermaid

A Place to Call Home (audiobook)

Blue Willow (audiobook)

Silk and Stone (audiobook)

Miracle (audiobook)

When Venus Fell (audiobook)

Coming in 2013: Shepherd’s Moon

Sweet Hush

by

Deborah Smith

Bell Bridge Books

Copyright

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons (living or dead), events or locations is entirely coincidental.

Bell Bridge Books

PO BOX 300921

Memphis, TN 38130

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-935661-24-5

Print ISBN: 978-0-9802453-0-1

Bell Bridge Books is an Imprint of BelleBooks, Inc.

Copyright © 2003 by Deborah Smith

Printed and bound in the United States of America.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

A hardcover edition of this book was published by Little, Brown & Co.in 2003.

A mass market edition of this book was published by Grand Central Publishing in 2004.

We at BelleBooks enjoy hearing from readers.

Visit our websites – www.BelleBooks.com and www.BellBridgeBooks.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Cover design: Debra Dixon

Interior design: Hank Smith

Photo credits:

ZM Photography @ Fotolia

:Ehs:01:

Orchards

In your orchard, you welcome all blooming souls,

Green spirits, gold dreams, red passions—

Sour Shaws, Auburn Delilahs,

MacLand Tarts, Osmo Russetts, Candler Wilds;

A thousand whispers of trees long gone—

Forgotten apples, lost in the earth.

But yours survive, my dear, strong Hush;

Your hopes beckon, soft and sweet;

Your trees grow forever, where two hearts meet.

—A poem written for the second Hush McGillen, 1899, by her husband.

Prologue

I’M THE FIFTH Hush McGillen named after the Sweet Hush apple, but the only one who has thrown a rotten Sweet Hush at the First Lady of these United States. In my own defense, I have to tell you the First Lady threw a rotten Sweet Hush at me, too. The exchange, apples notwithstanding, was sad and deadly serious.

“You’ve ruined my daughter. I want her back,” she said.

“I’ll trade you for my son,” I answered. “And for Nick Jakobek’s soul.”

After all, the fight wasn’t really about her or me, but about our sorely linked destinies and our respective children and our respective men and our view of what we were put in the world to accomplish with other people watching. Whether those people were a whole country or a single, stubborn family. There’s a fine line between public fame and private shame. For those of us who have something to hide, holding that line takes more of our natural energy than we want to admit.

So, standing in the White House that day with liquid, festering apple flesh on my hands like blood, I realized a basic truth: The world isn’t kept in order by politics, money, armies, or religion, but by the single-minded ability of ordinary souls to defend all we hold dear and secret about our personal legends, armed with the fruit of our life’s work. In my case, apples.

I walked wearily down one of the White House corridors we’ve all seen in magazines and documentaries. For the record, the mansion is smaller than it looks on television, but the effect is more potent in person. My heels clicked too loudly. My skin felt the weight of important air. History whispered to me, Hush, go home and lick your wounds and start over with your hands and your tears in the good, solid earth. I followed a manicured sidewalk outside into the winter sunshine, and then to the public streets. The guard at the gate by the south lawn said, “Can I help you, Mrs. Thackery?” as if I’d strolled by a thousand times. Fame, no matter how indirect or unwanted, has its benefits.

“I could use a tissue, please.” I only wanted to wipe a few bits of rotten apple off my jeans and red blazer, but he gave me a whole pack. Hush McGillen Thackery of Chocinaw County, Georgia, rated a whole pack of tissues at the White House guard gate. I should have been impressed.

I put my mountaineer fingers between my lips and whistled up a cab. I took that cab to the hospital in Bethesda, Maryland where in the 1950’s President Eisenhower’s doctors hid his heart trouble and in the 1980’s President Reagan’s doctors hid the fact that our old-gentleman leader had gone funny. It was a safe place to keep family troubles close to the soul and away from the rest of the country. I slipped in past a crowd of reporters with the help of the Secret Service, who hadn’t yet heard I’d splattered you-know-who with an apple.

I went to the private room where Nick Jakobek lay recuperating somewhere below the shore of normal sleep, his stomach and chest bound with bandages that hid long rows of stitches, his arm fitted with a slow drip of soothing narcotics, which he would sure as hell jerk from his vein when he woke up. I sat down beside Jakobek’s bed and cupped one of his big hands in mine.

People had sworn he was the kind of man who could do me no good outside of bed. A suspect stranger, not a Good Old Boy or a swank southern businessman, not One of Us. A man who had never tilled the soil for a living or sold a bushel of newly picked apples to an apple-hungry world or sat around a campfire drinking bourbon under a hunter’s moon. A man who knew more about ways

to die than ways to live. A man so cloaked in rumors and mysteries that even the President couldn’t protect his reputation. Without a doubt, people said, Hush McGillen Thackery would never stoop to love that kind of man, after loving such a fine man as her husband.

I’m here to tell you I did, he wasn’t, I wasn’t supposed to, but I do.

“This was never about you and me,” I whispered to Jakobek. “People just have to grow where they’re planted. That’s the last apple analogy I’ll offer you until you decide to ask for more. If and when. Just remember. Just believe me. You have earned your blessings.” I kissed him and cried a little. His mouth eased, but he couldn’t wake up.

“I hear that you and my wife had an unhappy meeting,” someone said. I turned and found the President gazing at me from the room’s doorway.

“I hit her with a rotten apple.” Not something you really like to tell a man who has his own army.

But the President only nodded. “She deserved it.”

I tucked a small crucifix of apple wood inside Nick’s unfurled hand, bent my forehead to his for a long, hard moment then left the room. It was time to go home to the fertile, wild mountains of Georgia, where I and everyone I loved—except Nick Jakobek and his Presidential relatives—belonged.

We all make ourselves up as we go along, until the tall tales of our lives grow around our weaknesses and humiliations like the tough bark of an apple tree. Call it public relations for the country’s good or call it making the best of a bad situation in a family or a marriage or a love affair, but either way, we root our lives in other people’s ideas of who we are, both public and private, both great and small.

But an apple, of course, never really falls far from its tree.

Part One

Chapter 1

EARN THE BLESSINGS. We McGillens had always had to earn our blessings on the cruel grace of the seasons and the hard red hope of ripe apples. Our legacy started in 1865 with Hush Campbell McGillen, a young Scottish woman whose husband, Thomas, died in pieces at the battle of Bull Run. We suspect Thomas McGillen was a Pennsylvania Scotsman in the service of the Union Army, but Great-Great-Great Grandmother Hush never admitted such a notorious thing after she came to enemy territory in the Appalachian South. She brought with her four half-grown sons and daughters, a mule, a wagon, fifty dollars, and a bag of apple seeds gathered from every orchard she’d passed between Pennsylvania and Georgia.

Hush The First had grown up growing apples in the old country, where her daddy managed an Englishman’s fruit trees. Hush knew how to site an orchard, how to make a graft take life on the root stock, how to draw bees covered in pollen every spring, how to store apples for months every winter. She understood an apple tree’s need for warm soil and good water and clear, cool skies; and the apple trees understood her. Like them, she had a yearning for land, the kind of good orchard land even a dirt-poor widow could claim for nothing. That land lay in the cradle of a wild mountain paradise called Chocinaw County, Georgia.

Hush The First found her way to a broad creek valley at the base of Chocinaw Mountain and Chocinaw’s sister mountains, Big Jaw and Ataluck. That valley was called The Hollow by mountain people, like the mysterious hollow at the base of a great, towering tree. It lay so deep in the laps of Chocinaw, Big Jaw, and Ataluck it could only be reached on foot, and so far from civilization nobody but a desperate person would want to try. The Hollow sat ten miles west of Dalyrimple, the courthouse seat of Chocinaw County (where everybody was unashamedly glad the War had ignored them,) twenty miles south of shell-shocked Chattanooga, Tennessee, a hundred miles north of burned-out Atlanta, and a thousand miles west of the Scottish lowlands where Hush had been born.

‘Nowhere’ had a better chance of being found on a map.

To add to its mystique, the Hollow was shunned by local folk as a valley of the dead. There, in a glen along the creek, lay buried the corpses of nearly fifty Union and Reb soldiers. They’d killed each other in a nasty mutual massacre only the year before Hush arrived. The mind-your-own-business mountaineers of Chocinaw County had buried the soldiers in shallow graves, right where they’d fallen. Dalyrimple’s most educated man, town founder Arnaud Dalyrimple—bartender, gambler, minister of the gospel and newspaper columnist—wrote in The Dalyrimple Weekly Courier:

The gloriously wild Hollow is as haunted as Mr. Abraham Lincoln’s own most personal Hell.

But Hush looked at the Hollow and saw apple country. The mountainsides protected it from high winds and gave shade from the blistering Southern sun; the mountain creeks and springs seeped water down to the Hollow’s big creek in a dependable supply. Most of all, groves of wild crabapples draped the lower hills like oases among the granite cliffs. Those tough little trees clung to the crevices between laurel shrubs and rock, blooming like mad. They knew a good home when they found one, and they knew the Hollow was meant for apples. “Apple trees do no’ mind a few bones, and the dead do no’ mind a few apples,” Hush said. She gave her fifty dollars for a deed to the Hollow’s two hundred acres, set up camp, cleared the soil, and planted her seeds.

Now, apples are the same as people. No two seeds are alike. Plant a hundred seeds and you’ll get a hundred unique apple trees—some good, some bad, but most ordinary, like anybody’s children. Hush knew only time and fate would sort out the curious mix she’d planted—Vandermeers from Pennsylvania, Colridge Yellows from Maryland, Spirit Reds from the Carolinas, and many more. There were hundreds of apple varieties in the cool eastern half of this country, then. Every small farm had an orchard, and every county had a breed of apple to call its own. Farmers waited to see what each season’s bees would bring them on fuzzy bee legs covered in pollen. They studied every offsprung seedling like pilgrims searching for a holy leader.

Maybe this one will be special. Maybe this one will be the queen mother of all apple trees.

Hush watched her trees for ten years, then twenty. By then her children had grown and gone, she’d added a room to her drafty log house, established a small lot of cattle and chickens and pigs, built a barn and bought two new mules. Her sons had hacked out a muddy wagon lane over to Dalyrimple and named it McGillen Orchards Road. Hush earned a meager living selling wagonloads of apples to the townsfolk every fall. But still, no special tree. Every spring she watched the bees flit back and forth between her tame orchard and the wild, seductive crabapples on the mountainsides. A daughter who had moved to Atlanta wrote to a friend: Mama still believes God In His Heaven will smile on the marriage of her trees and His.

As she grew old, Hush taught a granddaughter, Liza Hush McGillen, (known as the second Hush McGillen) to help her in the orchard. Together, they studied each year’s maturing young trees for The One. In the fall of 1889, they found it. There it was, in its first season of fruit—a strong, proud young tree standing right in the middle of the old burial ground of the dead soldiers, sprung up from their bones, bearing apples so sweet the juice burst in the mouth like sugar.

Hush and Liza Hush fell to their knees, crying and laughing and eating that wondrous fruit. Over the years that followed, they slivered twigs from the young tree’s branches, trained them onto root stock, and cloned the marvelous mama tree a hundred times, then two hundred, and more. Word traveled like love-hungry apple bees; people came to buy. Hush sold apples, and Hush sold grafted seedlings, and Hush sold Hush—her legend, that is.

Redder than an Arkansas Beauty, as long-keeping as a Ben Davis, juicier than a Jenny’s Eureka, sweeter than a Blush Delilah.

The Sweet Hush Apple.

Every generation before me earned the right to the name, and I’d had to, as well.

I was trained to grow the Sweet Hush by my Great Aunt Betty Hush (the fourth Hush McGillen,) who had owned the Hollow before my father. Betty had learned the apple business from her elder cousin, William Hush McGillen, (the third Hush McGillen, and the only one who happened to be male,) who had run the

famous Sweet Hush orchards during their first heyday, between 1900 and 1930. According to all the family stories, William Hush McGillen had been endowed with the expert business sense of a preacher pumping sinners for nickels. I liked to think I inherited his knack.

All of Chocinaw County sported Sweet Hush apple orchards during the reign of William Hush, and the widely seeded McGillen clan basked in comfortable homes with fine iron stoves in the kitchens and fast Model-T cars in the yard. William Hush and all his cousins sold apples by the ton and illegal homemade apple brandy by the barrel-full. Down in Atlanta, William’s sister, Doreatha McGillen, started the Sweet Hush Bakery Company. Every year the mountain McGillens sent thousands of the best Sweet Hush apples by mule wagon and train down to Doreatha, who stewed and pureed and spiced them into fillings for all manner of baked goods. Those delicious goods were hand-delivered to the city’s finest homes by white-suited black men in handsome, horse-drawn wagons with SWEET HUSH BAKERY on the sides in scrolling Victorian letters. Sweet Hush Deep Dish Apple Pies regularly appeared on the dessert board at the Governor’s mansion.

Then the Depression wiped out Doreatha’s bakery. Federal revenue agents from the Roosevelt administration broke up the McGillen liquor business (and our families, too—my proud grandfather and one of his cousins, both deacons in the Dalyrimple Baptist Church, were caught with their liquor stills and killed themselves rather than serve time on the chain gang.) But worst of all, the rise of modern refrigeration and long-range shipping turned local apples into a novelty, not a necessity.

Most of the great Southern orchards were gone by the time of my birth in 1962—chopped down, burned to their stumps, forgotten, unwanted, unloved. Potter Prides, Escanow Plumps, Sweet Birdsaps, Black Does, Lacey Pinks—all were extinct from the earth, and hundreds more like them. Gone forever. We McGillens continued to suffer one streak of bad luck after another (my own father died young of a heart attack, while chopping briars in the orchards) but we and our Sweet Hushes hung on by stubborn stems, refusing to give up in a world that had turned us aside for cheap Wisconsin Winesaps and ice-cold Japanese Mutsus.

Legends

Legends Hold on Tight

Hold on Tight Just a Little Bit Guilty

Just a Little Bit Guilty The Beloved Woman

The Beloved Woman Alice At Heart

Alice At Heart Heart of the Dragon

Heart of the Dragon Critters of Mossy Creek

Critters of Mossy Creek Diary of a Radical Mermaid

Diary of a Radical Mermaid Caught by Surprise

Caught by Surprise Stranger in Camelot

Stranger in Camelot At Home in Mossy Creek

At Home in Mossy Creek Charming Grace

Charming Grace Blue Willow

Blue Willow The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella

The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella On Bear Mountain

On Bear Mountain The Biscuit Witch

The Biscuit Witch Sara's Surprise

Sara's Surprise More Sweet Tea

More Sweet Tea The Apple Pie Knights

The Apple Pie Knights The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove

The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove Sweet Hush

Sweet Hush California Royale

California Royale Hot Touch

Hot Touch Miracle

Miracle The Stone Flower Garden

The Stone Flower Garden A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home Silk and Stone

Silk and Stone Honey and Smoke

Honey and Smoke Jed's Sweet Revenge

Jed's Sweet Revenge Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove

Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove The Kitchen Charmer

The Kitchen Charmer A Day in Mossy Creek

A Day in Mossy Creek Never Let Go

Never Let Go Summer in Mossy Creek

Summer in Mossy Creek On Grandma's Porch

On Grandma's Porch The Crossroads Cafe

The Crossroads Cafe Follow the Sun

Follow the Sun The Yarn Spinner

The Yarn Spinner A Gentle Rain

A Gentle Rain Reunion at Mossy Creek

Reunion at Mossy Creek