- Home

- Deborah Smith

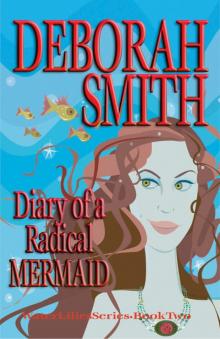

Diary of a Radical Mermaid Page 12

Diary of a Radical Mermaid Read online

Page 12

Her long, coral fingernails dug in. “I wonder if I could squeeze just right and make your larynx pop out.”

I squirmed. “Tara McEvers got herself killed pulling pranks on UniWorld. Wasn’t that a good lesson to the rest of you boringly obsessed activists?”

“Pranks? Tara was a hero.”

“Right. She hooked up with a boogeyman Swimmer and let him talk her into a goofy plot to blow up a research ship, then he betrayed her, so now she’s dead, and her daughters have no mother, and their boogeyman daddy may be out to kill them for some insane, possessive reason, and Jordan Brighton is in danger because of it all.”

She released my throat with a disgusted little shove. “Think whatever you want. UniWorld is scheming against Mers as well as Landers. Some of us are trying to prove it.”

I sucked down some air. “And then you’ll move on to other ludicrous theories, such as ‘Elvis — alive and hiding his webbed toes?’ and ‘Madonna — Mer, or just a pretentious twit?’”

“I’m wasting my time talking to you.” She dragged me to my feet. A pair of hunky boy toys appeared from nowhere and took me by the arms before I could make a break for the ocean. I moaned. The shore wasn’t more than a hundred yards from the hotel. If I could just get to that surf, get out into the deep, I’d swim the whole way back to Sainte’s Point if I had to. I had to get back to Jordan.

I felt Aphrodite, queen of the Amazon boobs, probing my thoughts and studying me. “Why, I do declare,” she said in a Spanish-accented southern drawl. “Scarlett has a heart.”

“Stuff it, Mammy.”

She laughed fiendishly.

And then I was hauled back inside.

* * * *

I should have known my nieces were up to no good.

“We’re going back to the mansion for a nap, Uncle Rhymer,” Stella announced, as a pretty afternoon sun blazed over the island beaches. The four of us sat on soft silk blankets under the shade of an oak, looking out at the beach and the ocean. The girls were nearly frantic to dive into the Atlantic, where young dolphins kept poking their blue-gray heads from the water and chattering, Come and play. Come and play.

Out at the island’s western point, Jordan, armed with his buffed fingernails and Uzi, had given me some rest time. He stood guard beside the remains of an old lighthouse, aided by a pod of dolphin elders who patrolled the island’s waters like guard dogs as a favor to us.

I turned a suspicious eye to Les Sleepy Femme du Threesome. “A nap, is it? I can’t recall a single time when you three have napped during full daylight.”

Isis pouted. “We might as well sleep. We can’t go swimming. We’re shriveling up.”

Venus added with a sad face and the slightest lisp, “The baby dolphins think we’re naught but sissies.”

“Dolphins are a bit cheeky that way. Pay no heed. All right, off to the house with you. But stay on the path and go straight inside. I’ll be there in a bit.”

Stella smiled, grabbed the younger ones by their hands, and they trotted up the sandy path through the deep arbor of giant oaks and draping moss. Squirrels, raccoons, birds, two lizards and several deer, who had all been nibbling bread from the girls’ palms, looked disappointed. Frowning, I watched until the girls disappeared

The mansion is naught but a stone’s throw from here. They’ll sing out if anything or anyone startles them.

I got up and paced, windblown and barefoot in old khakis and a thin cotton shirt, stomping web-toed prints in the sand. I pulled a slender, intricately carved pipe from my shirt pocket. I filled it from a leather pouch, lit the bowl with a good, god-fearing sulphur match, and took a deep draw. Mer-kind can no’ touch tobacco — it’s as deadly as a poison to our oxygen-rich lungs — but we do love our herbs. No, I’m not meaning your obvious cannibis, but rich, guarded mixtures of exotics from all over the world, blended by hand, given as gifts by proud Mer growers, guaranteed to mellow the most worried soul.

I puffed and inhaled, blew out and puffed again. I saw Moll’s worldly innocence in the smoke; I saw my sister’s smile. I saw the memory of the girl I’d loved and killed for decades before. But I saw nothing of the unknowable, unpredictable Orion. I emptied my pipe, brushed sand over the wisps of its leavings, then returned the pipe to a back pocket. There would be no mellowing of my mood anytime soon.

When I got back to the Bonavendier mansion I scaled the grand staircase two steps at a time and padded silently down a Picasso-adorned corridor to the girls’ suite for a quick check. I sensed them sleeping, sprawled like pale angels on a big bed they shared. Yes, the girls could broadcast illusions, could fool even the toughest Mer heart — that I knew because they were Healers, and Healers are so charismatic, when it suits them. But they and I had a military respect, an understanding, an agreement. I expected to find them snoozing innocently.

They were gone.

* * * *

Hyacinth swam swiftly through the sky-blue water, I typed, past the sign that read, DO NOT VENTURE BEYOND THESE BOUNDARIES, BY ORDER OF FINSTER’S ACADEMY OF MER-MISSES AND MER-SIRS, past the dozing tentacles of Octivant, the academy’s guard-dog octopus, and past the Reef of Giggly Silliness, which made a pretty coral crescent along the outer edge of Finster Academy’s magical underwater world. She knew only one thing: She had to get to the deep, dark, abyss that led to the Cave of the Argonauts, if she was ever to solve the mystery of Orion.

Orion. I groaned, then deleted the name from my laptop’s screen, and instead correctly typed the mystery of the dolphin queen. I nervously scruffed my bare foot over Heathcliff, who lay on his pillow beneath my table on the pier at Randolph Cottage. He dozed in the table’s shade, cooled by the bay breeze despite a hot afternoon sun. He’d been sleeping even more than usual. Winding down. I was worried about him.

Must concentrate. Must . . . write. Must stay focused.

The dolphin queen. The . . . dolphin . . . queen. But nothing popped into my head as a follow-up. I took a break and spent several minutes rearranging the folds of my floppy white sundress. When the words won’t flow, writing is like sitting in heavy traffic listening to static on the car’s radio. “Oh, who am I kidding?” I said aloud. “I’m only feigning normalcy. Working on the next book and pretending to be calm, just as if I haven’t been set down in Oz. Heathcliff, maybe I’ll just give up and carry you inside and try to perk you up with some tuna, and then get drunk on an entire six-pack of the first diet cola I can lay my hands on.”

Heathcliff snored on in tired disregard.

I forced my fingers back on the keyboard. Stop worrying about Heathcliff. Stop worrying about Rhymer and his nieces. Stop thinking about Orion. Stop thinking, period. Write. Go on, fingers. Type something.

Nothing happened. My fingers wouldn’t strike. They were on strike.

I sank back in my wicker chair, pulled my sunhat low over my face, and recited the last few paragraphs in a loud, muse-commanding tone. “Hyacinth had to get to the deep, dark, Abyss of Forever that led to the Cave of The Argonauts if she was ever to solve the mystery of the dolphin queen.” I took a deep breath and continued. “As . . . Hyacinth flicked her lovely pink tail fin and gathered herself for a burst of speed into the fearsome darkness, a hand grabbed her arm. Rapid-fire fingertips tapped on her skin, spelling out words in the secret underwater language that had been used by Finster students for generations. Hyacinth Meridian, don’t you dare go out there alone.

“Agggh. Barney, she thought. I should have known you’d follow me. Barnacle T. Tradvorius, Barney to his friends, scowled at her when she tried to pull away. Hyacinth slapped a hand on his bare shoulder and tapped out a fierce rebuke. Barnacle, you let go of my arm or I will . . .”

I halted, struggling. “I will . . . uh . . . I will . . .” I sighed. “I don’t know what she’ll do to him.”

“Pound him into crab snot!” a little voice supplied.

“Pound him into . . .”

I leapt up, grabbed my cane, and looked around wildly. I saw only some se

agulls and, out in the bay, the dorsal fins of a few dolphins who dropped by to chatter at me occasionally, like native hosts politely trying to teach their language to an immigrant.

“Who spoke?” I called. Silence. Chills ran down my spine. The voice had been small, childlike. Would Orion imitate a child? Was he about to rise from the water and attack me? Had he already attacked Rhymer and the girls, and now I was to be his next victim?

Not without a fight.

I knotted a fist to my chest and limped to the end of the pier, ferociously thumping my cane on the wide boards. Small monkeys pound sticks on the ground to make themselves seem more fierce; so did I.

“Who’s there!” I demanded, reaching the end railing and grabbing its weathered wood for support. “I’m not afraid of—”

I looked down.

Three small, beautiful faces looked up at me.

The smallest one gave an anxious mew. “Please don’t pound us into crab snot, Miss Revere.”

Scottish. The little voice had a Scottish lilt.

Rhymer’s nieces. “What in the world . . . don’t worry. I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to yell at you. Come out. Climb up. There’s a ladder right over—” A terrible thought struck me. “Is everything all right? Where’s your uncle?”

The largest of the girls looked up at me solemnly. “He thinks we’re napping. I’m sure he’ll come after us soon. May we visit until then?”

“Of course you may visit! Climb up!”

I gazed in wonder as they swam to the pier’s ladder. They moved like glimmers of sunlight flashing on the water, graceful and effortless, arms and legs barely flicking, their bodies undulating. I’d never seen any human being swim the way they did. The smallest one climbed up first, a perfect little doll in a yellow swimsuit, her skin creamy pale, her eyes bright green and extraordinarily large. Wavy, black hair streamed all the way to her knees. When she stepped off the ladder her delicate feet hardly made a sound. I stared at elongated toes linked by gossamer webbing the color of peaches.

And at beautiful little hands with peach-hued webbing between the fingers.

Toto, we’re not in Kansas anymore.

The older girls were just as ethereal, with manes of black hair and huge green eyes and webbed feet and webbed hands. The tallest one wore a black swimsuit, the middle one, jade green. The one in black said quietly, “I’m Stella. This is my sister, Isis, and our little sister, Venus. We do hope we’re not intruding, Miss Revere. We love your books.”

“I’m honored. Please, please, call me Molly.”

That brought smiles. Their eyes gleamed.

Venus, the smallest one, spotted Heathcliff beneath the table. “Oh, dear, oh, dear, old kitty, old, sick kitty,” she moaned. “I’ll just pet the old, sick kitty a bit—”

“No,” Stella ordered, and Isis grabbed her by the hand. Clearly, something about my cat was forbidden. Perhaps little Venus had an allergy to animals. But then all three girls leaned down and studied Heathcliff with expressions I can only describe as wistful and tormented. They swiveled those gazes to me, then to my cane. They trembled.

Stella exhaled. “If you don’t mind us asking . . . how were you hurt?”

I explained briefly, and delicately, that a truck had hit my parents’ car when I was not much older than they. That my leg had been badly injured, and my parents killed.

“And you’ve been sick at times,” Stella said. “In other ways.”

“I have a small problem with my blood. But I’m fine.”

“No, you’re not,” Isis said bluntly. “Some people have blood diseases from being part-Lander. They don’t understand why they’re so sickly, but it’s because they’re Mers and don’t know it.”

Venus looked up at her sisters. Her expression was agonized. “Couldn’t we —”

“No,” Stella said firmly but gently. “Not right now.”

Venus whimpered.

I didn’t know what they were trying to tell me, or each other. I didn’t like discussing my blood so I changed the subject to a seahorse of a different color. “So, you’re fans of my books?”

They nodded eagerly. “We want to know what happens to Hyacinth in the next novel,” Stella said.

“Did you know you were a Mer when you wrote the first Hyacinth book?” Isis asked.

“No, but I suppose I suspected it, deep down. I just didn’t know what to call myself.”

“But you knew you were special.”

I smiled sadly. “I knew I was different.”

Their eyes widened. Different, yes. That connected. “You were so sad and lost when your parents died,” Stella put in. “You even wanted to die.”

I froze. “I beg your pardon?”

“We can feel the story inside you,” Isis said flatly. “The time you tried to drown yourself in the ocean — but someone special saved you.”

“Now, girls, I never tried to —”

“The year after the accident,” Stella supplied. “You could barely walk. You couldn’t even swim anymore. You were so lonely. Friends of your parents took you to stay with them. You wanted to die. You went into the water. You lived in a small part of your mind then, shut off from everything else. But you didn’t drown — you couldn’t drown, not like a Lander — and you remember an extraordinary moment when arms gathered you, and long hair floated around you, and a very old, very beautiful voice said inside your mind, The water is your friend. The water can never hurt you. And you lived from then on. But you weren’t sure why, or what for.”

“How do you know that about me?”

“I can feel it. We all can.” The three girls nodded in unison. Venus added solemnly, “It was Melasine The Old One who rescued you. She knew you were special.”

I sank down in my chair and said nothing, a knot in my throat. They crowded around me. “About Hyacinth,” Stella said. Apparently, being rescued by the founding mother of mythological mermaids was just chitchat.

I recovered enough to say, “What would you like to know about her?”

Stella looked at me sadly. “I’d like to know what she finds beyond the Abyss of Forever. I want to know if there’s anything on the other side.”

Isis peered at me, frowning. “I’d like to see her escape from school and have her pet stingray electrocute anyone who tries to stop her. I like revenge.”

Venus clasped a hand to her heart. “I want to know if she’ll ever discover what became of her parents. Won’t her parents please, please come back from the Disappearing Sea?”

Their wistful requests left me speechless again. They didn’t have to sing inside my mind. I knew how it felt to be an orphaned child. “I promise you this much,” I said gently. “Hyacinth will have a family again. She’ll be happy again, some day.”

We heard the distant rumble of an engine. Across the bay, a sleek speedboat zoomed toward us. Rhymer.

“Oh, crap,” Isis said. “Uncle Rhymer is boiling mad. He’ll never let us out of his sight again.”

“He’s very strict,” Venus whispered to me. “We adore him, but he is awfully frightful.”

“Better him being frightful than our own father trying to kill us,” Isis intoned.

Stella hissed at her and cut her eyes at their little sister, who looked horrified. Isis sulked at the rebuke. Venus teared up.

I stood. The chicken of the sea morphed into a protective Mer mother hen. “Move aside, girls,” I said crisply, “I’ll talk to your uncle.” I planted myself in front of them. My heart pounded. I could already see the grim set of Rhymer’s jaw. I cleared my psychic throat and sang out silently, These children are desperate for your approval and affection. Don’t you dare lecture them for visiting me.

Rhymer thundered inside my head, Approval and affection will do them no good if they’re dead. You’re a lure they can’t afford.

Lure? A lure? I didn’t lure them here.

Nor did you chase them away, I see.

What harm has been done? Please, let us visit.

Did t

hey sing to you? Did they touch you? Did they lay hands on Heathcliff?

No. Why would they? What are you talking about —

If they sing, Moll, he’ll hear them. And he’ll come.

They didn’t sing, but I don’t understand —

“Come aboard,” Rhymer said loudly, as he swung the speedboat into place beside the pier. “Girls. Into the boat with you. Not a word. Into the boat.”

The girls looked up at me with quiet regret. I nodded, defeated. “It was very nice to meet you all. When things are better, I’ll tell you everything you want to know about Hyacinth.”

Stella sighed. Isis pouted. Venus moaned and reached toward me. That small, beautiful hand, laced in see-through webbing that folded like invisible silk when the fingers were closed, opened like a diaphanous wing. It took all my will power not to place my open hand against the magic of hers. “Your mother,” I said hoarsely, “is with mine. They live in the most beautiful lagoon of the Disappearing Sea. They want us to smile and be happy.”

Venus’s eyes widened, then filled with joyful tears. She leaned forward. “Melasine sings to us sometimes,” she whispered. “I’m sure she’s very fond of you and glad she rescued you.” Venus and the others climbed down the ladder and into the boat. Rhymer gazed up at me, frowning, his eyes dark and hooded. Stay here and stay safe, Moll. Don’t call to them. It’s for your sake as well as theirs. And mine. Stay safe, Moll. I don’t want to lose any other people I love.

I couldn’t even form an answer. As he gunned the boat and headed back toward Sainte’s Point I stood there on the pier with my hand still held out to Venus, to Stella and Isis, and to him, pledging a troth to mysteries and magic and love I had only imagined, before.

Had I been saved by the ancient and wonderful Melasine years ago? I’d always thought it was a delusion. A mermaid off Cape Cod? And yet, I knew it was true. The water is your friend. The water can never hurt you, she’d said. I’d survived on those words from then on, though I wasn’t sure why, or what for.

Until now.

Meanwhile, Back in the Caribbean

Legends

Legends Hold on Tight

Hold on Tight Just a Little Bit Guilty

Just a Little Bit Guilty The Beloved Woman

The Beloved Woman Alice At Heart

Alice At Heart Heart of the Dragon

Heart of the Dragon Critters of Mossy Creek

Critters of Mossy Creek Diary of a Radical Mermaid

Diary of a Radical Mermaid Caught by Surprise

Caught by Surprise Stranger in Camelot

Stranger in Camelot At Home in Mossy Creek

At Home in Mossy Creek Charming Grace

Charming Grace Blue Willow

Blue Willow The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella

The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella On Bear Mountain

On Bear Mountain The Biscuit Witch

The Biscuit Witch Sara's Surprise

Sara's Surprise More Sweet Tea

More Sweet Tea The Apple Pie Knights

The Apple Pie Knights The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove

The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove Sweet Hush

Sweet Hush California Royale

California Royale Hot Touch

Hot Touch Miracle

Miracle The Stone Flower Garden

The Stone Flower Garden A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home Silk and Stone

Silk and Stone Honey and Smoke

Honey and Smoke Jed's Sweet Revenge

Jed's Sweet Revenge Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove

Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove The Kitchen Charmer

The Kitchen Charmer A Day in Mossy Creek

A Day in Mossy Creek Never Let Go

Never Let Go Summer in Mossy Creek

Summer in Mossy Creek On Grandma's Porch

On Grandma's Porch The Crossroads Cafe

The Crossroads Cafe Follow the Sun

Follow the Sun The Yarn Spinner

The Yarn Spinner A Gentle Rain

A Gentle Rain Reunion at Mossy Creek

Reunion at Mossy Creek