- Home

- Deborah Smith

A Gentle Rain Page 12

A Gentle Rain Read online

Page 12

Raw eggs? Everybody traded a worried look, then looked at me. "It's okay, calm down," I told them. "It'll taste good. It's a fancy recipe. You won't know it's got raw eggs in it."

Karen gave me a nod of appreciation. "I'll be right back." She headed toward the back. porch door, the route to the chicken house.

"Be careful," Bigfoot called. "I saw a rat snake outside there a few minutes ago. It was big enough to eat a ... a rat. And it likes raw eggs!" For all his size, Bigfoot was scared of snakes.

Karen turned at the door and smiled at him. "Have you ever seen a snake large enough to eat a caw?"

Bigfoot turned pale. "No."

"I have."

She went on out the door.

We all looked at each other, again. Mac turned to Lily and asked solemnly, "They have s-snakes that big up n-north?"

"I don't think so. Do they, Ben?"

"Naw. She's talkin' about South America, I think."

Roy gave me a bewildered look. "Isn't this south America?"

"No, this here is ... I tell you what. Tonight, I'll pull up a map on the computer, and I'll show you."

"South America is south of Mexico," Joey told everybody. "Ben used to go there, a lot. To work."

I gave him a little look, and he ducked his head in apology. No talking about wrestling.

All the hands gaped at me. "Ben, did you ever see a snake big enough to eat a cow?" Possum asked. He looked ready to crawl under the table.

"Nope. Look, y'all don't need to worry about giant snakes. I promise. They're not gonna hide on a boat to Miami, or sneak over the border in Texas, or take the bus cross-country from Tijuana. They're not coming here."

The group relaxed a little.

Mac nodded to everyone proudly. "N-nothing scares K-Karen. Not giant s-snakes. Not r-raw eggs. Nothing. She's a special little girl."

Lily smiled and nodded. "She makes her own bed, and she washes her own dishes, and she cleans her own commode. And at night, sometimes, we sit at the kitchen table and I watch her paint pictures. She keeps trying to get me to paint some pictures, too, but I'd rather watch her."

"She likes the baskets I m-make," Mac reported. "My split bamboo b-baskets? I t-told her how I 1-learned to make `em when I was a little bboy and how Nanny Bee taught me-"

"Nanny Bee was the cook at the Tolbert house at River Bluff," Lily supplied. "She said she made baskets just like her great-great-great grandmother did in Africa. My grandma was the housekeeper there, and I helped grandma clean, so Nanny Bee tried to teach me how to make African baskets, too, but I couldn't do it. But she said Mac was a natural. Karen says so, too."

Mac's smile widened. "Karen says I'm c-carrying on a t-tradition as old as c-civi ... civili.. zation."

Lily leaned in and lowered her voice as if afraid the outside world might overhear. "Karen asked me why Mac doesn't show off his baskets to people. She said the next time there's a craft show in Fountain Springs we should take Mac's baskets to sell. I told her what Glen says. That Mac's a Tolbert, and Tolberts don't sell baskets by the road like gypsies. Glen says people will think Mac's stupid and can't do real work. When I told Karen that, she got all of Mac's baskets out of the closet and set them on top of the kitchen cabinets. She said there's nothing stupid about making fine baskets. She said Mac's baskets belong in a museum. So there!"

I listened worriedly. They doted on Karen like she'd lived at the ranch all her life. Every day it was `Karen does this and Karen does that.' Joey felt the same way. She talked to Joey about food, music, art and all sorts of things in her solemn Yankee voice. She played the harp for him every afternoon. Joey just glowed.

Karen might be the best medicine for his ailing heart.

And for Mac and Lily's child-loving heart.

And for my lonely one.

Which really worried me.

Kara

Riding the range

"Pssst," Lula hissed from the hall outside Ben's office. "Com'ere, Karen. I wanta show you something private that Ben don't like to talk about."

I was in the midst of packing food for a luncheon on the prairie. That was my wry take on it. Actually, I was about to haul lunch to Ben and the hands, somewhere deep in the forests and pastures of the Thocco Ranch. I was excited about the adventure.

But the lure of Ben's office was irresistible. I crept down the narrow hall as if he might have surveillance cameras. Lula, who served as his secretary and bookkeeper, stood just outside the partially open door.

I halted. "Lula, I can't, in good conscience, go inside his private office without his permission."

She snorted. "I wasn't invitin' ya. I may be a lot of things, but I'm not a sneak. Sorta. Na-,N; here. I just want to show you these. `Cause I know Ben comes across like some hard-ass dude who's stuck in his ways. But look here."

She handed me a sheaf of award certificates. As I read through them, my mouth gaped. "Oh, my," I whispered. "Oh, my."

Lula grinned and elbowed me. "I knew those'd make you hot. Now go and be nice to the boy." Chortling, she took the certificates from me, retreated into his private lair, and shut the door.

Ben

The beef

"Jesus says go yonder," Dale yelled at a clutch of cows, moseying them with her waving hands and her cow pony. She rode a little bay Cracker mare she'd named Bug.

Bug was named that way because she scurried after cows with a paddle-footed racking gate that made her look like a scurrying June bug. Dale loved Bug almost as much as she loved Roy and Jesus. Bug's saddle was hand-tooled with embossed crosses and scripture numbers. Roy had borrowed two hundred dollars from me one Christmas to get Bug's saddle customized. Dale cried with joy when she unwrapped it. Her and Roy were all smiles from Christmas right up to New Year's.

"Bring them calves back along the fence line," I told Cheech and Bigfoot over a walkie talkie. We were moving five hundred head into the east-ranch forest, where they could spend the hottest days drowsing in the shade of giant live oaks. Them trees were saplings when George Washington said he couldn't tell a He. They'd been sheltering cattle since pioneer ranchers sold their herds to Spanish Cuba. Runaway slaves had hid among `em. Yanks and Rebs had camped in their shade. The trees had looked up at the sky when John Glenn rocketed into space from Cape Canaveral. They were living history markers. They held the stories of ghosts and tribes and whole generations in their roots.

Cheech and Bigfoot coon-walked their horses toward the runaway calves. The calves watched, hypnotized. There's something about a slinky, gliding Cracker coon walk that soothes a bovine heart. To one side, a mama quail and her brood made a bee line from one fence row to another, scurrying through the veil of dust kicked up by shuffling hooves.

I let my hogwire fences grow up in hedges and wildflowers. That's environmentally smart, the agricultural experts told me. That's common sense, my Cracker-Seminole ghosts whispered.

The cattle used the overgrown fence rows for shade and windbreaks. Wild critters used them for homes. Quail, rabbit, coons, squirrels, songbirds, turkeys-I'd seen everything come out of the fence rows. I swear, some days a fence hedge delivered more entertainment than a clown car.

"Five Two Nine," Mac called. I looked over. He stood in the middle of the cows, patting their red haunches as they went by. He pointed at one. "Five Two N-nine's lost her t-tag. And so has S-seven Four Eight and Two Three T-two."

Flat-out magic. How he could not only tell them look-alike cows apart, but remember which had which tag number. I just saw one more fat mama bovine. But Mac saw each cow and each calf, and each was special to him.

Another covey of quail crossed the pasture grass at a quick doublestep. Dust swirled from a bare spot. I made a mental note to re-seed the pasture. Ranching isn't just about managing livestock, it's about farming. High-protein grass makes high-protein beef Like feeds like.

Harmony. You can't make a living off nature unless you let nature make a livin' off you.

My walkie talkie crackled again. "I'll be therewith the c

huck wagon, at noon," Karen said.

"We don't call it a chuck wagon. We call it a four-wheeler."

"Ye of little imagination."

"Ye of way too much imagination," I countered.

She laughed. The sound crackled all the way through me. Even over a walkie talkie she had a great laugh.

I made a mental note to spruce up before lunchtime. My straw hat was soaked in mosquito spray. Sweat trickled down my legs inside my stained khakis. Forget jeans. Aworking cowboy in Florida wears the thinnest cotton pants he can. And tank tops. And suntan lotion, even if you've got tough, one-quarter Indian skin. And sunglasses. The wraparound kind. Some days I looked like a lifeguard on horseback.

But I smelled like something dead on the beach.

Damn. Karen showed up an hour early, her red hair stuffed up under a wide straw hat with a daisy band, which Lily had given her. Her chuck wagon-one of the ranch's four-wheelers-pulled a little metal trailer, which she'd loaded with ice chests, boxes of supplies, and the portable charcoal grill off the back porch. Lily sat amongst all that stuff in a lawn chair, grinning and waving at us with one hand.

With the other hand, Lily held the gray mare's lead rope. The mare looked calm enough until she saw me and the herd of red-and-white Hereford cows, most of them with calves. The mare threw her head back, snortin', and nearly dragged Lily off the trailer.

Karen hopped off the four-wheeler and grabbed the lead. Us men folk had to stay back or risk turning the mare into an equine snapping turtle. Mac and I watched worriedly as the mare skittered around under some oaks, kilda dragging Karen and Lily with her. Finally, they got her stopped. She stood under the trees, blowing hard and staring at the cows. Karen tied her lead to a thick tree limb on an oak the size of a house.

"There goes that oak," I deadpanned. "I wonder how far she'll drag it?"

Karen wiped sweat from her face beneath odd-looking sunglasses. I think the frames were made from pieces of Brazil nuts. "If we never take her out of her pen, she'll never become socialized."

"Around here, we don't believe in socialized horses. They just try to organize the other horses and demand better hay."

"I'm impressed. Your definition of socialism is somewhat apt. However, I hope we can agree that there's great good in collective action. One for all and all for one."

"Oh? Ever heard of a little collective action called a `stampede?"'

"Very amusing. I'll set up lunch, now"

Our usual lunch on the range consisted of cold fruit pies, protein bars and any kitchen leftovers that could be put between sandwich bread.

Karen's lunch on the range consisted of seafood paella and grilled vegetables.

As everybody chowed down on that feast, Possum looked over at her and said, "From now on, if you want to call the four-wheeler a chuck wagon, you go right ahead."

Everybody nodded.

She smiled.

I have to admit, the highlight of my day was lazing under an oak watching Karen put supplies away after lunch. She moved good. Her parts moved good. The whole package, it all moved good.

Lily and Mac dozed on a blanket nearby. Everybody else had pretty much collapsed under the shade trees beside their napping horses.

"For the record," I said, "I don't approve of siestas."

"You should. Afternoon naps make for a healthy lifestyle."

"Sorry, you're not gonna get any modern health habits out of a Cracker cowboy."

"Really? You're a slave to self-destructive cowboy traditions, hmmm?"

"Yep. Ever heard of Bone Mizell?"

"Is that a person or a syndrome? Can it be treated?"

I pulled the brim of hat lower over my eyes but not so low I couldn't look at her. "Bone Mizell was the greatest Cracker cowboy who ever lived. Late eighteen hundreds. Worked for some of the biggest ranchers in the state. They say Bone could mammy-up a whole herd."

"Excuse me?"

"Match cow to calf. Remember markings, brands, whatever." I wagged a finger toward Mac, sleeping. "Mac can do it. It's a rare talent."

Her gaze quickly went to Mac, sleeping. "I want to see that."

"Hang around after lunch. You'll see. Anyhow, about Bone. Wild man. Hard drinker, hard life. But godawmighty, what a character. People loved him. They say he once ran a wild Cracker heifer out of the brambles and bit her on the ear to brand her as his stock. And then there was the time a rich Yankee died on a fishing trip near Kissimmee. Nothing to do in the heat but bury him right there.

"Some time later, his widow paid Bone to dig up the corpse and ship it north. But Bone, having a Cracker's sense of humor, dug up an of cowboy friend and sent that corpse, instead. Widow held a big fancy memorial service over the body; she never knew the difference. Bone said he did it `cause his friend had always wanted to travel."

"Oh, please. That must be a tall tale. Folklore."

"I'm just sayin'. He was famous. You look him up. Remington painted him."

"Fredric Remington?"

"Yep. For one of the big New York magazines. Titled, `A Cracker Cowboy.)"

"Wait a minute. Is that the print you've got framed in the living room? That bearded derelict on a bow-necked cattle pony standing in a swamp?"

ey.

"I apologize. I am impressed."

"By what? Me owning a Remington print?"

"By the legacy you represent."

"Aw"

"What became of Bone Mizell?"

"Died with his boots on."

"Riding the range?"

"Naw. Drunk in the Fort Ogden train depot."

"Oh, I see."

"They found him dead on the floor. So the story goes, when the doc pronounced him, it was just so hard to believe that one fellow said, `Doc, ain't you gonna test him?' And the doc said, `Don't have to. I can tell he's ninety proof"'

Her mouth quirked, but a frown got the best of her. "Surely you don't want to emulate such self-destructive behavior."

"Naw, not the hard living. But -I like his spirit."

"So you claim you're disinterested in modern ideas?"

CC " Yep.

"A reactionary of the most iconic sort."

"I know you mean that in a good way."

She sat down on an ice chest beside me. "That must be why you've been nominated for so many environmental stewardship awards."

I lifted my hat an inch. "Who says?"

"Lula showed me a few of them. Never fear, she didn't allow me inside your office sanctuary. Ben, those awards are-"

"Aw Nature lovers. I let `em come out and take a few tours of the wild woods, and 41 return they say nice things about me. That's all."

"Oh? You've accomplished some amazing things in the decade since you bought this ranch." She counted on her fingertips. "Building new irrigation ditches to utilize the creek while, at the same time, halting run-off of fertilizers and animal wastes. Allowing natural hedgerows to re-establish themselves along your fence lines to provide cover and food sources for wildlife. Re-seeding portions ofyour pastures with high-protein grass and legume crops specifically meant to feed deer, turkey, and other wildlife. Encouraging large bird nesting, including egrets and bald eagles. Allowing wildlife rehabilitators to release black bears and even a few native panthers in your forest. Very impressive for a man who claims he's just an aw-shucks rancher."

"Aw, shucks."

"Ben, I'm not flattering you. I'm sincerely impressed."

I sat up. "But see, here's the thing: I'm not doing anything special. I'm just doing what's right."

"That's what makes you special."

"I wish it'd make me a little more money."

"It will. In the long run ..."

"There may not be a long run. But that's just between you and me."

She searched my face. "I thought there was a good bit of profit in beef cattle ranching."

"Some years, yeah. Some not. Tell everybody to go back to low-carb diets. I almost had my hay baler paid off."

"Perhaps beef cattle aren't yo

ur best product. If you're sincerely interested in doing what's best for the planet-"

"Oh, no. Don't tell me you're against eaten' red meat."

She hesitated, frowning. "Don't take it personally."

I stood, whipping my hat off and slapping it on one leg. "I'm not sellin' my herd. Drop this subject right now. I don't want to hear it."

"You don't have to sell the herd overnight. Just ... transition ...

"Into what? Raising beef cattle is all I know. It's what I do best. All I need're a few breaks to get back in the black." I gestured at her t-shirt. It had a humpback whale on it. "What I don't need is an ignorant do-gooder giving me lectures about how to save the whales."

She stood, looking huffy. "My whales and your Herefords are connected by an intricate ecosystem. They're not a separate issue."

"Well, when a humpback swims up the Little Hatchawatchee and starts eating grain at the feeding troughs, I'll put my brand on it."

"You stubborn, knee-jerk-"

Whoosh. Swish of gray, thundering hooves. A quick breeze.

The gray mare raced by us, trailing her lead rope, or at least, what was left of it where she'd chewed through the nylon. Her ears flattened, her muzzle curled back, she bared her teeth. She hated the cows, and she was about to show `em who was boss.

"See there," I said to Karen, as I ran to save the herd. "Even that mare's a meat eater."

Kara

I leaned my chin on my folded hands, gazing sadly at the gray mare through the top rail of her corral. "We have to have a talk about a little psychological problem called `transferal of hostility."' I spoke to her in Portuguese. I didn't want anyone to know I was conducting a therapy session. "Yes, it can be emotionally satisfying to foist your anger onto innocent and helpless bystanders. But ultimately, the only one who suffers is you." I paused. "Although I suppose there might be some disagreement on that point, from the perspective of the five cows you bit."

She snorted softly, as if enjoying the fond memory.

I cleared my throat. "Luckily, they'll all recover with the help of a little antibiotic ointment. The fact that you only inflicted surface wounds tells me you were merely `acting out.' You're just looking for attention. But attacking others is not the way to get it? Understand?"

Legends

Legends Hold on Tight

Hold on Tight Just a Little Bit Guilty

Just a Little Bit Guilty The Beloved Woman

The Beloved Woman Alice At Heart

Alice At Heart Heart of the Dragon

Heart of the Dragon Critters of Mossy Creek

Critters of Mossy Creek Diary of a Radical Mermaid

Diary of a Radical Mermaid Caught by Surprise

Caught by Surprise Stranger in Camelot

Stranger in Camelot At Home in Mossy Creek

At Home in Mossy Creek Charming Grace

Charming Grace Blue Willow

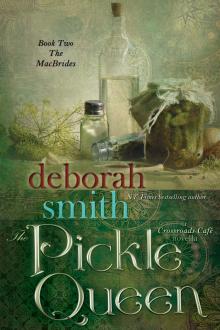

Blue Willow The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella

The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella On Bear Mountain

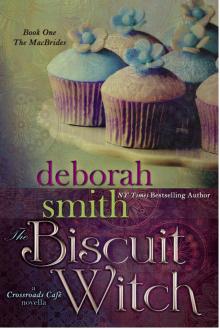

On Bear Mountain The Biscuit Witch

The Biscuit Witch Sara's Surprise

Sara's Surprise More Sweet Tea

More Sweet Tea The Apple Pie Knights

The Apple Pie Knights The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove

The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove Sweet Hush

Sweet Hush California Royale

California Royale Hot Touch

Hot Touch Miracle

Miracle The Stone Flower Garden

The Stone Flower Garden A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home Silk and Stone

Silk and Stone Honey and Smoke

Honey and Smoke Jed's Sweet Revenge

Jed's Sweet Revenge Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove

Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove The Kitchen Charmer

The Kitchen Charmer A Day in Mossy Creek

A Day in Mossy Creek Never Let Go

Never Let Go Summer in Mossy Creek

Summer in Mossy Creek On Grandma's Porch

On Grandma's Porch The Crossroads Cafe

The Crossroads Cafe Follow the Sun

Follow the Sun The Yarn Spinner

The Yarn Spinner A Gentle Rain

A Gentle Rain Reunion at Mossy Creek

Reunion at Mossy Creek