- Home

- Deborah Smith

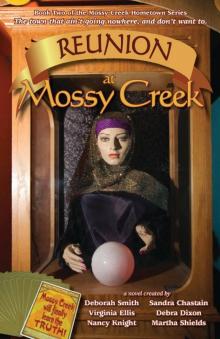

Reunion at Mossy Creek Page 2

Reunion at Mossy Creek Read online

Page 2

What do reunions mean to you?

Reunions? I guess Katie Bell means family reunions. I only graduated from Bigelow High School two years ago, so my class certainly wouldn’t have had a reunion yet.

I think I’d better not answer that question. It’d hurt Daddy’s feelings for sure. The McClure family reunion, held at a state park just north of Mossy Creek every year, has always been pure torture for me. The McClure relatives feel sorry for poor, plain little Josie. They think I don’t hear them talk while I’m helping Mama set out the food, but I do. I don’t like going to reunions. I wish I never had to go to another one.

When you look at the empty spot where the high school stood, what person comes to mind, and why?

Mama, of course. She’s told me the story of how the homecoming queen crown was stolen from her so many times, I know it by heart. Mama was about to be crowned queen of Mossy Creek High when the school mascot, a ram—which in my opinion is just a fancy name for a boy sheep—shot out of the stands with sparklers tied to its wool. That sheep left a path of mayhem and destruction that’s affected Mossy Creek to this very day.

What is the most hurtful and publicly humiliating thing that ever happened to you in high school?

That one’s easy to answer. It was when Derk Bigelow asked me to the Christmas dance my junior year at Bigelow High, and I stupidly believed he meant it. He’d just broken up with his girlfriend, Marjorie Tutmeir, after all, and even though Derk is from the richest family in Bigelow County—he’s a second cousin of Governor Ham Bigelow—he’s not the cutest puppy in the litter, if you know what I mean.

Mama proudly bought me the most beautiful green velvet dress in Miss Martin’s Boutique in Mossy Creek. I would rather have kept my business to myself, but of course Mama had to brag to everyone that I needed the dress because I was going to the Christmas dance with a Bigelow—though I have to admit I secretly enjoyed their reactions. They were shocked that Josie McClure, of all people, could manage such a feat. A girl they considered such a wallflower that surely I must’ve taken root by then. Unfortunately, that publicity meant that everyone in Mossy Creek found out about my ultimate humiliation as well.

The night of the dance, I waited at the double doors of the high school gym like Derk had suggested since he didn’t want to drive all the way up into the mountainous northern end of Bigelow County at night to get me. I noticed other kids staring at me, some snickering together, but they’d always done that if I happened to show up at an extracurricular school function, which was as rare an occurrence as roses in January.

When Derk showed up at seven on the dot, Marjorie was on his arm. He hadn’t broken up with her at all. Turns out I was the victim of a bet he’d made with a couple of other boys, members of the cruel Fang and Claw Society, no doubt. Would I be stupid enough to dress up and wait for him at the gym door?

I was. Derk made his buddies pay him right there in front of me.

If I’d only known then that Derk was a Scorpio-Rat . . . and what that means. After Derk, I started studying astrology so I could recognize people when I saw them coming. Astrology is just another of my peculiar interests. I guess it doesn’t matter now, but I never went to another school event after that.

What is the one thing that happened to you in high school that made you the person you are today?

That’s an easy one, too. My tenth grade Home Ec class. That was where I discovered the zen of decorating.

I fold napkins.

Like me, that’s more special than it sounds.

* * * *

When you live in the mountains, you grow up hearing tales of Bigfoot. Any mountains. From California to Maine, from Ohio to Georgia, Bigfoot or Sasquatch has made an appearance. I'd long suspected he was made up by mothers who used the legend to keep their children from wandering the steep terrain and getting lost.

Once I realized that Bigfoot was simply the Appalachian version of the boogie man, and that the biggest dangers I faced in the wooded coves were black bears and the elements, I was out the door of my parents' house and climbing the ridges up Mount Colchik to my playground, my freedom, my sanctuary. Colchik made a wild green hummock against the northern horizon of Mossy Creek. Up on Colchik, I was queen.

When I began studying feng shui—led to it by an article about the Eastern philosophy of decorating in an issue of Martha Stewart Living—I learned that mountains are really sleeping dragons, and the peaks, the humps of their backs. Not only is dragon’s breath the best chi—or energy—there is, but Snakes and Dragons get along extremely well. That’s important because I’m a Snake, astrologically speaking. Blending the Western and Eastern astrologies—which I always do—I’m a Cancer-Snake. A shy, secretive, home-loving recluse. A wallflower, in other words, though I prefer to think of myself more as a mountain laurel, perhaps, that blooms high up on the cold slopes, mostly unseen.

But I knew before I’d ever heard about feng shui, or even astrology, for that matter, that there was no danger for me in my mountains. Every time I disappeared into the primal forests, I felt as if my friend the Dragon were folding safe, warm arms around me. I feared neither black bears—which I occasionally spotted—or Bigfoot, whom I never saw.

Until . . .

I began seeing the footprints last spring, just before the dreaded Miss Bigelow Contest, which Mama forced me to enter. I needed the Dragon’s strength quite a bit then and visited Mount Colchik every day. The sun’s warmth had penetrated the thick hardwood foliage enough by May to keep the earth thawed.

The first footprint was in the mud beside the pool beneath a waterfall so deep in the mountains it had no name as far as I knew. I swam in the pool during the summer months. I passed the footprint off as a freak incident. Animal tracks falling together in a familiar pattern. Sort of like seeing shapes in the clouds.

By the time I found the fifth print several months later, I suspected some children were playing pranks. My pool was several hours hike from the nearest road or farm, and I’d never seen anyone else—child or grownup—wandering my mountain. Still, I’d found the pool when I was ten years old. Other children could’ve found it, too.

The possibility depressed me. Not that children might be clowning around. Children did those kinds of things. But I felt as if my privacy had been violated. Colchik was my mountain. This was my pool. I didn’t want to share my space with anyone. The possibility of a real Bigfoot existing never occurred to me, not in any serious way. How many humans had bare footprints that measured close to eighteen inches?

None of the explanations frightened me, and none could keep me from finding solace in my mountains. Especially after the Miss Bigelow Contest when Mama railed night and day about me losing. The forest was the only place I felt welcome, the only place I felt part of the world around me. Nature didn’t care where you placed in any kind of contest. It treated you with the same nonchalance with which it treated every other creature. Mama, however, was another matter.

As I’ve said, Mama was Mossy Creek High School’s last homecoming queen . . . but she was never crowned. The high school burned down that night, dooming Mama’s glorious reign. She’s never gotten over it. So for the last nineteen years she’s been trying to make me into the beauty queen she never got to be.

There’s only one problem. Me. Wallflowers get crowned only in fairy tales.

Mama, however, didn’t find it easy to face reality. She groomed me for the Miss Bigelow Pageant from the day I was born, though I cringed every time she mentioned it. She was determined that her daughter would be queen of the entire county, and she dedicated her life to this end. I had every kind of grooming, etiquette, and dancing lesson she could find within a day’s drive. She was constantly telling me how to walk, how to stand, how to wave, how to smile. Nothing I did was ever good enough. It certainly wasn’t good enough to win the Miss Bigelow crown. When I came in dead last, the entire reason for Mama’s existence fell in like a house of cards. She blamed me, of course. She’d done her part.

* * * *

Mama began sipping Daddy's best whiskey. Mama hated winter, hated the cold weather that was coming. She made me feel like she hated me, too. I’d never felt so depressed. Never felt so ugly, so totally worthless. So I escaped up on Colchik even more. That’s where I finally met Bigfoot.

I sat on the edge of the pool under Josie Falls—as I’d named them—and pondered what to do. I didn’t want to go back home—ever. Why should I? I was a grown woman. Nineteen years old. Graduated from high school. Mama didn’t want me. Every time she looked at me, she started crying, cursing, or drinking. On the other hand, I couldn’t leave home because I had no way to support myself. No skills beyond textbook Martha Stewart decorating, and decorating jobs required at least some college education. I’d checked the Internet on the library computer.

As I stared into water so clear I could see trout swimming six feet down, so cold it formed a crust of ice around the edges at night, the water seemed to whisper to me, inviting me in. You’re needed here, Josie. The mountain loves you. Stay here and stop fighting your loneliness.

The falls had never lied to me, so I listened, even though I knew I was depressed and should back away. As the afternoon began to wane, I became convinced the whispers were right. I wanted to merge with my mountains, to melt into the tears that spewed from its side.

I rose stiffly, my muscles cramped from inactivity and the cold rock I sat on. Slowly, I undressed. I’d always swum nude, though never in weather cold enough to hurt me. I’d never been embarrassed or ashamed of my nakedness here. I was down to my underwear when out the corner of my eyes, I saw movement in a shrub nearby. Looking up—way up—I saw a man’s face.

I turned to run. My feet caught in the clothes I’d just removed. With a cry, my arms flailing for support, I fell into the ice-cold water. Needles stabbed into every part of my body, disorienting me so much I couldn’t tell which way was up. I tried to surface but sank like a lead doll. I couldn’t move. I couldn’t feel my hands or feet.

Then the world turned black.

* * * *

The next thing I knew, I awoke to blessed warmth. Maybe this is a dream, I murmured. I sighed and snuggled into my blanket cocoon.

“Did you say something?”

The deep voice directly above me made my eyes spring open. A mountain of a man leaned over me. The biggest, longest-bearded man I’d ever seen. His large hand probed my face. “You’re not running a fever, thank God. Can you hear me? Do you understand what I’m saying?” His voice rumbled more than spoke, so deep it came from his belly instead of his throat. A dark red, puckered scar covered his forehead and left eye. There was probably more to it, but that’s all I could see above his beard.

“Are you an angel?” I asked.

His eyes narrowed. “Very funny.”

He certainly didn’t look like the traditional representation of an angel, but since I’d studied feng shui and the philosophies it was based on, my spiritual path had meandered along many nontraditional trails. “I’m not trying to be funny,” I whispered. “Am I alive?”

“Of course you’re alive.” He straightened. His head seemed to brush the raw plank ceiling of his cabin. “Though it’s a miracle. If I hadn’t fished you out when I did. . . .” He heaved a sigh and moved away from the bed.

I rolled over in my cocoon of warm blankets so my gaze could follow him. Three strides of his long legs took him clear across to the other side of the room to a stone fireplace. A roaring fire blazed in the natural stone hearth under a black cauldron suspended from an iron bar running across the top. He stirred whatever simmered in the pot. It smelled wonderful.

“You saved me?” My mind felt as if it, too, were wrapped in a cocoon.

“Somebody had to.”

“Where am I?”

“My cabin.”

“I mean where is that, in relation to Josie Falls?”

He straightened from the hearth. “Josie Falls?”

“I named them. Do they have a name already?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Then I officially name them Josie Falls.”

“What made you decide to take a swim today? You haven’t been in the pool since early September.”

“How do you know that?” But the idea that he’d been watching me didn’t alarm me. Rather, it felt . . . warm . . . intriguing.

“Well, I’m not a stalker. When people start dropping their clothes by a pool, I assume they’re about to go swimming. I don’t stay around to watch.”

“Who are you?” I tried to sit up, but weakness and the tight cocoon hampered me. He stepped over and easily lifted me against the bed’s rough headboard. His head really did almost touch the ceiling, and his shoulders were as wide as a century-old hemlock. “Gracious, you’re big.”

He shoved both hands back through his thick black hair. “Good thing. A smaller man would never have been able to carry you two miles over rough terrain.”

I leaned over to look at his feet. “Ohmigosh. You’re the Bigfoot!”

He growled something and turned back to the hearth. I didn’t know then that he’d been called the awful name ever since he’d grown into his size twenty-two shoes.

“I’ve seen footprints ever since April.”

He scooped some of the cauldron’s contents into a bowl. “Who are you?” I repeated. “Why are you living way up here alone?”

After pouring something from a brown bottle into a tin cup, he brought that and the bowl over to the bed. Looking from them to me, he finally sat down and lifted the spoon to my mouth.

I turned my head away. “I want answers.”

“Eat. You put your body through a traumatic shock and you need nourishment.”

I was alone with a mountain of a mountain man who spoke like a college professor. Whoever he was, even hidden behind the beard he was clearly no backwoodsman—and a good deal older than me. As a shy wallflower, I should’ve been frightened out of my wits, but somehow I knew he would never hurt me. My astrological instincts, you might say. Emboldened by my certainty, I glared at him. “Not until you tell me who you are.” I struggled to free my arms from the blankets. “Let me out of this thing.”

He sighed, put down the bowl, and loosened the coverings enough for me to fight my arms free. As I did, the blankets fell to my waist, and I looked down to see nothing but my thermal undershirt.

I yanked the blankets up. I wasn’t feeling that bold.

Hot blood stung my cheeks.

He coughed and stood up. Yanking open a chest of drawers, he grabbed a flannel shirt and tossed it on the bed. “Awfully big, but you can wear it.”

Once he retreated to the other side of the cabin to stare into the fire, I let the blanket drop and quickly donned his shirt. The soft, thick material swallowed me, suffusing my brain with an unknown yet primordial and familiar scent—the musky warmth of a man. Rattled by my perception, I folded back the sleeve cuffs four times so I could find my hands, then fastened every button except the collar. Finally, I announced, “I’m decent.”

He returned to the bed, picked up the bowl and once again lifted the spoon to my mouth. “Eat, and I’ll tell you who I am.”

I opened my mouth.

He slipped the spoon inside. “My name is Harold Rutherford. I bought this place two summers ago.”

I swallowed the thick flavorful stew. “This is delicious.”

“Thank you.”

“Why?”

His lips, half-hidden by his beard, curved upward. “Why is it delicious?”

He had a sense of humor. I fell half in love with him at that moment. “No. Why did you move so far up into the mountains?”

He hesitated, then deliberately turned his scarred face toward the fire. “To hide.”

“Those scars look like burns. Were you burned?” I reached out a hand. “When?”

At my first touch, he stood abruptly, upsetting the tin cup still sitting on the bed.

I caught the cup before it could spill, then licked the drops that sloshed onto my fingers. “Whiskey. You’re a real mountain man, I guess. From what I hear, they use whiskey to treat everything.”

“I thought it might warm you up.”

“You accomplished that without whiskey.” I couldn’t believe the huskiness of my voice. It sounded almost . . . sultry. Me. Josie McClure.

He must’ve heard it, too, because he turned back to me. “Josie. . .”

“You know my name.” It didn’t surprise me.

The fire popped, drawing his attention. It took a moment before he looked at me again. “Look under the pillow beside you.”

I reached under the feather pillow to find my navy blue sweater.

“You left it beside the falls about a month ago.”

I didn’t have to look at the tag to know my name was written there in indelible ink. Mama couldn’t get over the fact that I wasn’t in grade school anymore. “I remember. It grew warm that day, and I took it off before I waded in the pool. I was halfway home before I realized I’d forgotten it. Since it was so late, I decided to come back for it the next day. When it wasn’t there, I figured some animal had stolen it to pad his den.” I grinned. “I was right.”

He was not amused.

I dropped my gaze to the sweater in my hands. “Were you . . . watching me that day?”

He seemed to struggle with himself, then finally said, “Yes.”

“I see.” I lifted the sweater to my nose and inhaled. It smelled faintly like me, but mostly like warm wool, and mountains . . . and Harry. I smiled. Harry. What an appropriate name. I didn’t feel the least bit bad about shortening his name without his permission. Then I shivered, realizing I was already able to recognize his scent.

“What in the world are you thinking?” he asked.

“That you smell good.”

He hesitated, then said firmly, “Stop joking.”

Legends

Legends Hold on Tight

Hold on Tight Just a Little Bit Guilty

Just a Little Bit Guilty The Beloved Woman

The Beloved Woman Alice At Heart

Alice At Heart Heart of the Dragon

Heart of the Dragon Critters of Mossy Creek

Critters of Mossy Creek Diary of a Radical Mermaid

Diary of a Radical Mermaid Caught by Surprise

Caught by Surprise Stranger in Camelot

Stranger in Camelot At Home in Mossy Creek

At Home in Mossy Creek Charming Grace

Charming Grace Blue Willow

Blue Willow The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella

The Pickle Queen: A Crossroads Café Novella On Bear Mountain

On Bear Mountain The Biscuit Witch

The Biscuit Witch Sara's Surprise

Sara's Surprise More Sweet Tea

More Sweet Tea The Apple Pie Knights

The Apple Pie Knights The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove

The Silver Fox and the Red-Hot Dove Sweet Hush

Sweet Hush California Royale

California Royale Hot Touch

Hot Touch Miracle

Miracle The Stone Flower Garden

The Stone Flower Garden A Place to Call Home

A Place to Call Home Silk and Stone

Silk and Stone Honey and Smoke

Honey and Smoke Jed's Sweet Revenge

Jed's Sweet Revenge Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove

Silver Fox and Red Hot Dove The Kitchen Charmer

The Kitchen Charmer A Day in Mossy Creek

A Day in Mossy Creek Never Let Go

Never Let Go Summer in Mossy Creek

Summer in Mossy Creek On Grandma's Porch

On Grandma's Porch The Crossroads Cafe

The Crossroads Cafe Follow the Sun

Follow the Sun The Yarn Spinner

The Yarn Spinner A Gentle Rain

A Gentle Rain Reunion at Mossy Creek

Reunion at Mossy Creek